Getting NASA’s Pluto mission off the ground took blood, sweat and years

The world tracked the New Horizons’ spacecraft with childlike glee as it flew by Pluto in 2015. The probe provided the first ever close-up of the place that many of us grew up considering the ninth planet. Pluto revealed itself as a fascinating world, with a shifting surface (SN: 12/26/15, p. 16), a hazy atmosphere (SN Online: 10/15/15) and a heart of nitrogen ice (SN Online: 9/23/16).

But the course of space exploration never did run smooth. In Chasing New Horizons, Alan Stern — New Horizons’ principal investigator and chief champion — and his coauthor, team member David Grinspoon, share their recollections of how a band of scrappy planetary scientists got a mission to the farthest reaches of the solar system off the ground. Over the course of a decade and a half, Stern and colleagues in the “Pluto Underground” fought first to get a Pluto mission taken seriously by NASA, then to keep it alive through budget woes, political battles, stiff competition from other mission proposals and outright cancellations.

Even if you followed the flyby closely and think you know this story, the book divulges details that will surprise you. Come for the sweeping tale of wonder and exploration; stay for the gaggle of planetary scientists celebrating on Bourbon Street once their mission finally got the green light.

Science News talked with Stern about the book, what it’s like to be “Mr. Pluto” and what’s next for New Horizons, which is currently in hibernation cruising through the Kuiper Belt. The interview that follows has been edited for length and clarity.

SN: Almost half of the book is about the fight to get the New Horizons mission approved. Why was it important for you to focus on that?

Stern: If you look at the 26-year span, from 1989 [the year the American Geophysical Union meeting devoted the first conference session to the subject of a Pluto mission] to 2015 when we got there, almost precisely half of that time was back and forth trying to get a mission to Pluto.

It’s rare for the public to get to see the behind the scenes of how difficult it is — how much competition there is, how many things come out of left field, how much scientists with a goal or objective in mind really have to have persistence to make it happen.

SN: You write that by the time the mission teams were being assembled, you were already known as Mr. Pluto. When did you start feeling like Mr. Pluto yourself?

Stern: Somewhere in the ʼ90s, when we were going through this maze of twists and turns to get a mission to Pluto. Every time we’d have a reversal, and I’d have to go fight for it again, I started to feel like I was putting on my Mr. Pluto hat.

I’m typecast that way now. You know, I’ve been on 29 different space missions, to almost every planet in the solar system. Only one of them was to Pluto, but that’s the one, maybe the only one, I’m known for. It’s like being on the cast of Gilligan’s Island, they only remember you for the one thing, no matter how much else you’ve done. Which is fine [laughs]. I love Pluto, no question, but it’s not like that’s all I did in the past three decades.

SN: What’s next for New Horizons?

Stern: We emerge from an almost six-month hibernation period on June 4. Our next flyby is taking place on New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day with a small Kuiper Belt object that we’ve nicknamed Ultima Thule, which is a building block of planets like Pluto.

It’s going to just be spectacular, scientifically. And so our team is really up to our eyeballs in flyby planning and preparations.

SN: How long can the spacecraft keep going after that?

Stern: New Horizons has the fuel and power to go on for decades, and it’s very healthy. And there’s a lot more science to do in the Kuiper Belt. In fact, there is some science that the spacecraft is capable of doing that no other spacecraft can. There are some kinds of unique astrophysics that even the James Webb [Space Telescope, due to launch in 2020] and the Hubble can’t do, that we can do.

New Horizons is really is an amazing resource. There’s no other spacecraft planned to fly to these great distances again. So we want to make sure that science benefits to the maximum extent.

SN: There’s a scene in the book, right before the Pluto flyby, when a journalist asks how you’re going to feel at the end of the mission — will there be a sort of grief at the culmination of all this work. Now that you’re on the other side, how does it feel?

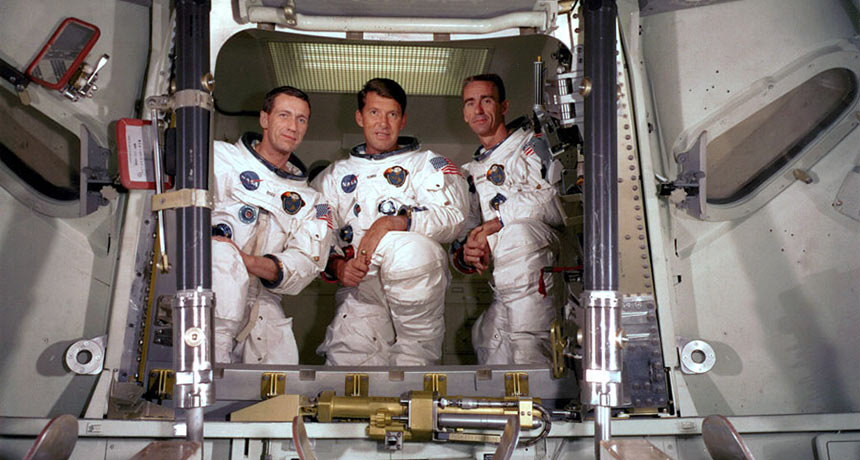

Stern: A lot of people in the mission team, as we were finally bearing down on Pluto, started to express that kind of concern. Frankly, we’d been so busy I didn’t have time to think philosophically about “what after.” I was thinking about catching up on my sleep, seeing my family more, what discoveries would we make. But I wasn’t thinking about, what do you do after your Apollo 11? What do you do after you’ve scaled your Everest?

As it turns out, a lot of those concerns just sort of washed away with the success of the flyby and the spectacular scientific discoveries at Pluto. Now I and other people on our team look back on it and say, “I was a part of something that really made a difference.” You can’t ask for much more than that.