Selfish genes hide for decades in plain sight of worm geneticists

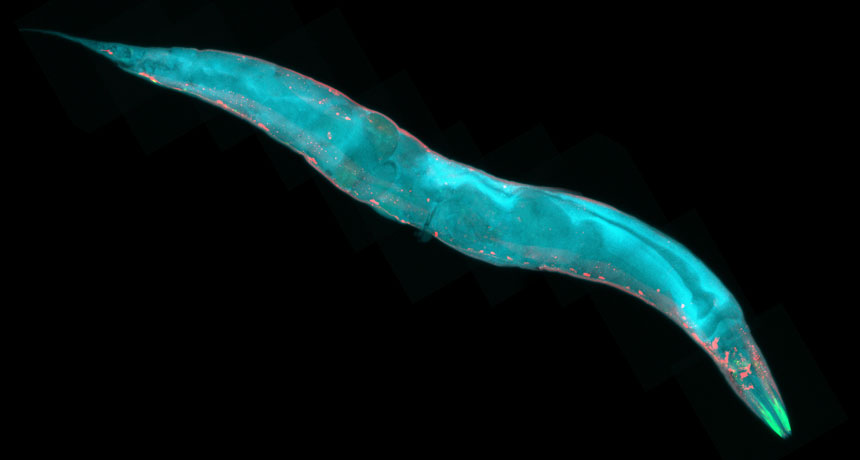

A strain of wild Hawaiian worms has helped unmask long-studied genes as just plain selfish. The scammers beat the usual odds of inheritance and spread extra fast by making mother worms poison some of their offspring.

Biologists have for decades discussed how two genes in the familiar lab nematode Caenorhabditis elegans might help embryos build their organs. Working with a little-studied wild strain, however, caused a rethink of the genes’ supposedly beneficial role “that flipped it on its head,” says UCLA geneticist Leonid Kruglyak.

Instead of doing some body sculpting, the gene sup-35 doses the eggs with a toxin that will kill them after fertilization, two postdocs in the Kruglyak lab discovered. The toxin gene doesn’t poison itself out of the gene pool because it’s linked to a partner, pha-1, that lets embryos manufacture an antidote. Embryos die unless they inherit a copy of the antidote gene in either egg or sperm, and so the poison-antidote duo can spread unusually fast through populations.

Making a mom on occasion poison some of her offspring doesn’t benefit her but certainly helps the genes. Thus the long-known sup-35 and pha-1 form what’s called a selfish genetic element, Kruglyak’s team proposes May 11 in Science.

That analysis is “very clearly accurate,” says evolutionary geneticist Jack Werren of the University of Rochester in New York. The idea that a gene could behave selfishly, promoting its own spread regardless of its host’s interests, was once controversial (SN: 3/19/16, p. 12). But as molecular biology techniques have improved, researchers have found more and more examples. Many of the most dramatic forms of selfishness, the murderous cheats, come from bacteria, so Werren welcomes the C. elegans scam as a rare case discovered in animals.

Kruglyak’s lab has described an earlier example in C. elegans: a gene that doses sperm with a toxin that kills embryos unless an antidote gene rescues them. Finding a second selfish element in the nematode, he says, suggests that these may not be as rare in animals as people have thought.

The big community of researchers regularly studying C. elegans had missed discovering the selfish role for a simple reason: The main lab strain of nematodes carries the selfish element, explains study coauthor Eyal Ben-David. Whenever the standard strain mates or self-fertilizes (the species has both males and hermaphrodites), all the offspring inherit sup-35 and pha-1. Researchers see no weird die-offs.

In the Kruglyak lab, however, Ben-David and fellow postdoc Alejandro Burga were doing a project that required crossing the usual lab nematodes with the DL238 strain from Hawaii. In its natural state, this strain has somehow escaped invasion by the selfish sup-35/pha-1 pair.

A series of oddities in interbreeding the disparate strains pushed the researchers to reconsider the two genes. For instance, much higher percentages of offspring died in mixed-parent crosses than the routine few percent in same-strain pairings. And when Ben-David and Burga looked at the genes in the Hawaiian strain isolated from the wild, sup-35 and pha-1 just weren’t there.

That was a shock. Earlier experiments in the lab strain had shown that disabling pha-1 caused death in offspring — which it certainly does. The feeding tube of the dying embryos was not forming properly, so researchers at first speculated that the gene controlled tube development. Later work suggested a more nuanced role for it, Ben-David says, but the overall hypothesis remained that the genes helped regulate embryo development. The Hawaiian strain changed that thinking: “How is this wild isolate alive and happy without a gene that’s supposed to be essential for development?” Kruglyak wanted to know.

A better way of interpreting the old experiments, he and his colleagues suggest, is that the embryos died because pha-1 wasn’t providing the antidote to the sup-35 toxin. “No one had previously considered the possibility,” says David S. Fay of the University of Wyoming in Laramie, who has done much of the work exploring the role of these genes. “All the data, including a lot of our previous published and unpublished findings, seem to fit the [selfish gene] model perfectly,” he says. And perhaps the highest praise: “I wish we had somehow come up with the solution ourselves.”