Dawn spacecraft maps water beneath the surface of Ceres

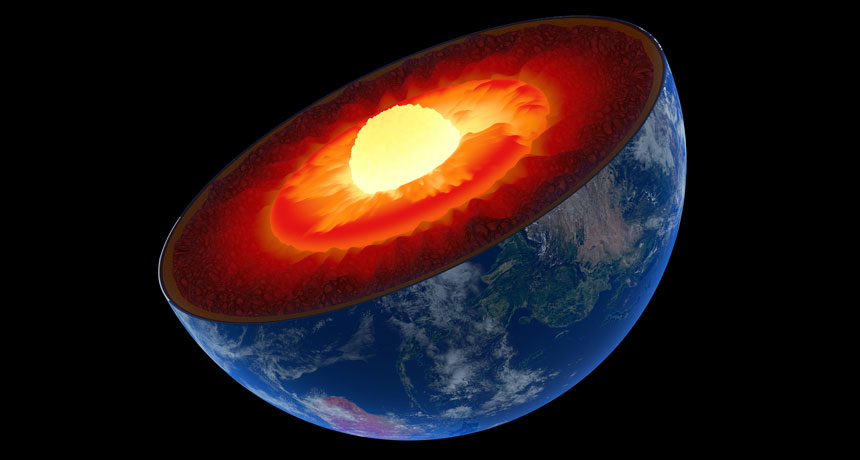

Water ice lies just beneath the cratered surface of dwarf planet Ceres and in shadowy pockets within those craters, new studies report. Observations from NASA’s Dawn spacecraft add to the growing body of evidence that Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, has held on to a considerable amount of water for billions of years.

“We’ve seen ice in different contexts throughout the solar system,” says Thomas Prettyman, a planetary scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson and coauthor of one of the studies, published online December 15 in Science. “Now we see the same thing on Ceres.” Ice accumulates in craters on Mercury and the moon, an icy layer sits below the surface of Mars, and water ice slathers the landscape of several moons of the outer planets. Each new sighting of H2O contributes to the story of how the solar system formed and how water was delivered to a young Earth.

A layer of ice mixed with rock sits within about one meter of the surface concentrated near the poles, Prettyman and colleagues report. And images of inside some craters around the polar regions, from spots that never see sunlight, show bright patches, at least one of which is made of water ice, a separate team reports online December 15 in Nature Astronomy.

“Ceres was always believed to contain lots of water ice,” says Michael Küppers, a planetary scientist at the European Space Astronomy Center in Madrid, who was not involved with either study. Its overall density is lower than pure rock, implying that some low-density material such as ice is mixed in. The Herschel Space Observatory has seen water vapor escaping from the dwarf planet (SN Online: 1/22/14), and the Dawn probe, in orbit around Ceres since 2015, spied a patch of water ice in Oxo crater, though the amount of direct sunlight there implies the ice has survived for only dozens of years (SN Online: 9/1/16). The spacecraft has also found minerals on the surface that formed in the presence of water.

But researchers would like to know where Ceres’ water is. Knowing whether it is blended throughout the interior or segregated from the rock could help piece together the story of where Ceres formed and how the tiny world was put together. That, in turn, could provide insight into how diverse the worlds around other stars might be.

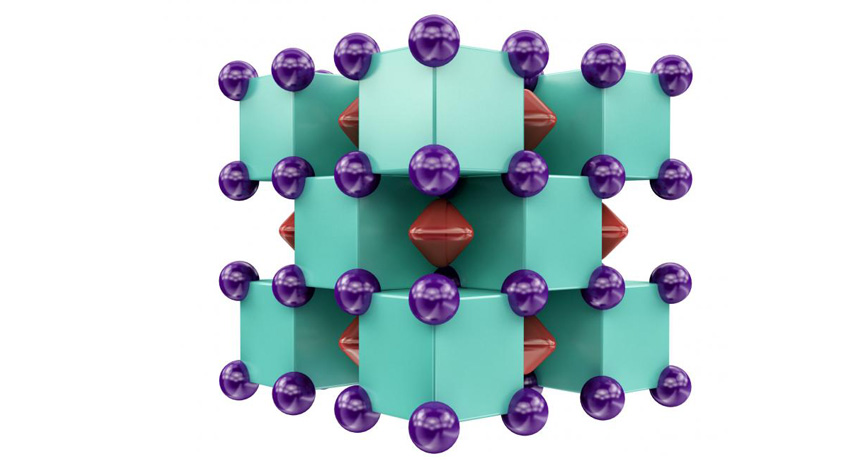

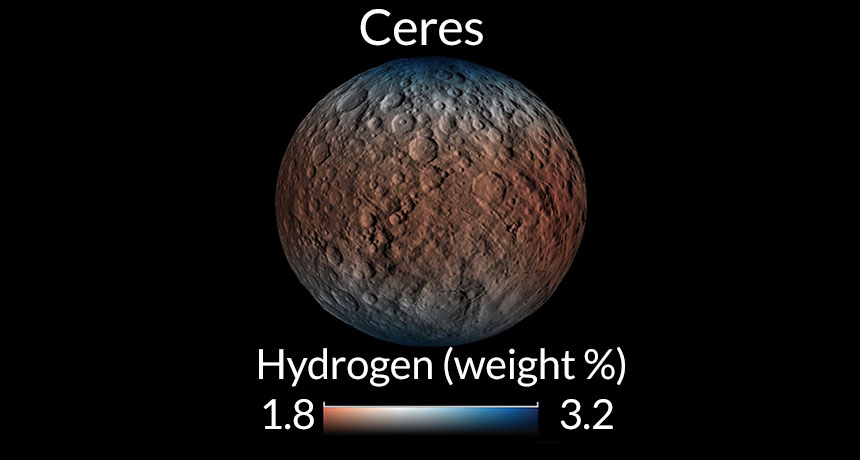

To map the subsurface ice, Prettyman and colleagues used a neutron and gamma-ray detector onboard Dawn. As Ceres is bombarded with cosmic rays — highly energetic particles that originate outside the solar system — atoms in the dwarf planet spray out neutrons. The amount and energy of the neutrons can provide a clue to the abundance of hydrogen, presumably locked up in water molecules and hydrated minerals.

Finding patches of ice was a bit more straightforward. Planetary scientist Thomas Platz and colleagues pinpointed permanently shadowed spots on Ceres, typically in crater floors near the north and south poles. The team then scoured images of those locations for bright patches. Out of the more than 600 darkened craters they identified, the researchers found 10 with bright deposits that could be surface ice. One had a chunk sticking out into just enough sunlight for Dawn to measure the spectrum of the reflected light and detect signs of water.

Water vapor escaping from inside the dwarf planet likely falls back to Ceres, where some of it gets trapped in these cold spots, says Platz, of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany.

Just because there is water doesn’t mean Ceres is a good place for life to take hold. Temperatures in the shadows don’t get above –216° Celsius. “It’s pretty cold, there’s no sunlight. We don’t think that’s a habitable environment,” Platz says. Although, he adds, “one could mine for future missions to get fuel.”

Ceres is now the third major heavily cratered body, along with Mercury and the moon, with permanently shadowed regions where ice builds up. “All the ones we’ve got info on to test this show you’ve accumulated something,” says Peter Thomas, a planetary scientist at Cornell University, who is not a part of either research team. Those details improve researchers’ understanding of how water interacts with a variety of planetary environments.