Live antibiotics use bacteria to kill bacteria

The woman in her 70s was in trouble. What started as a broken leg led to an infection in her hip that hung on for two years and several hospital stays. At a Nevada hospital, doctors gave the woman seven different antibiotics, one after the other. The drugs did little to help her. Lab results showed that none of the 14 antibiotics available at the hospital could fight the infection, caused by the bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Epidemiologist Lei Chen of the Washoe County Health District sent a bacterial sample to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The bacteria, CDC scientists found, produced a nasty enzyme called New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase, known for disabling many antibiotics. The enzyme was first seen in a patient from India, which is where the Nevada woman broke her leg and received treatment before returning to the United States.

The enzyme is worrisome because it arms bacteria against carbapenems, a group of last-resort antibiotics, says Alexander Kallen, a CDC medical epidemiologist based in Atlanta, who calls the drugs “our biggest guns for our sickest patients.”

The CDC’s final report revealed startling news: The bacteria raging in the woman’s body were resistant to all 26 antibiotics available in the United States. She died from septic shock; the infection shut down her organs.

Kallen estimates that there have been fewer than 10 cases of completely resistant bacterial infections in the United States. Such absolute resistance to all available drugs, though incredibly rare, was a “nightmare scenario,” says Daniel Kadouri, a micro-biologist at Rutgers School of Dental Medicine in Newark, N.J.

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria infect more than 2 million people in the United States every year, and at least 23,000 die, according to 2013 data, the most recent available from the CDC.

It’s time to flip the nightmare scenario and send a killer after the killer bacteria, say a handful of scientists with a new approach for fighting infection. The strategy, referred to as a “living antibiotic,” would pit one group of bacteria — given as a drug and dubbed “the predators” — against the bacteria that are wreaking havoc among humans.

The approach sounds extreme, but it might be necessary. Antimicrobial resistance “is something that we really, really have to take seriously,” says Elizabeth Tayler, senior technical officer for antimicrobial resistance at the World Health Organization in Geneva. “The ability of future generations to manage infection is at risk. It’s a global problem.”

The number of resistant strains has exploded, in part because doctors prescribe antibiotics too often. At least 30 percent of antibiotic prescriptions in the United States are not necessary, according to the CDC. When more people are exposed to more antibiotics, resistance is likely to build faster. And new alternatives are scarce, Kallen says, as the pace of developing novel antibiotics has slowed.

In search of new ideas, DARPA, a Department of Defense agency that invests in breakthrough technologies, is supporting work on predatory bacteria by Kadouri, as well as Robert Mitchell of Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology in South Korea, Liz Sockett of the University of Nottingham in England and Edouard Jurkevitch of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. This work, the agency says, represents “a significant departure from conventional antibiotic therapies.”

The approach is so unusual, people have called Kadouri and his lab crazy. “Probably, we are,” he jokes.

A movie-worthy killer

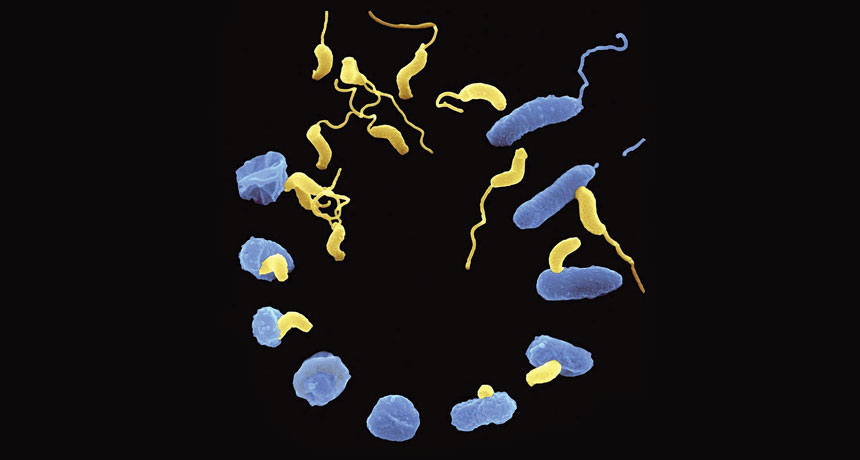

The notion of predatory bacteria sounds a bit scary, especially when Kadouri likens the most thoroughly studied of the predators, Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, to the vicious space creatures in the Alien movies.

B. bacteriovorus, called gram-negative because of how they are stained for microscope viewing, dine on other gram-negative bacteria. All gram-negative bacteria have an inner membrane and outer cell wall. The predators don’t go after the other main type of bacteria, gram-positives, which have just one membrane.

When it encounters a gram-negative bacterium, the predator appears to latch on with grappling hook–like appendages. Then, like a classic cat burglar cutting a hole in glass, B. bacteriovorus forces its way through the outer membrane and seems to seal the hole behind it. Once within the space between the outer and inner membranes, the predator secretes enzymes — as damaging as the movie aliens’ acid spit — that chew its prey’s nutrients and DNA into bite-sized pieces.

B. bacteriovorus then uses the broken-down genetic building blocks to make its own DNA and begin replicating. The invader and its progeny eventually emerge from the shell of the prey in a way reminiscent of a cinematic chest-bursting scene.

“It’s a very efficient killing machine,” Kadouri says. That’s good news because many of the most dangerous pathogens that are resistant to antibiotics are gram-negative (SN: 6/10/17, p. 8), according to a list released by the WHO in February.

It’s the predator’s hunger for the bad-guy bacteria, the ones that current drugs have become useless against, that Kadouri and other researchers hope to harness.

Pitting predatory against pathogenic bacteria sounds risky. But, from what researchers can tell, these killer bacteria appear safe. “We know that [B. bacteriovorus] doesn’t target mammalian cells,” Kadouri says.

Saving the see-through fish

To find out whether enlisting predatory bacteria might be crazy good and not just plain crazy, Kadouri’s lab group tested B. bacteriovorus’ killing ability against an array of bacteria in lab dishes in 2010. The microbe significantly reduced levels of 68 of the 83 bacteria tested.

Since then, Kadouri and others have looked at the predator’s ability to devour dangerous pathogens in animals. In rats and chickens, B. bacteriovorus reduced the number of bad bacteria. But the animals were always given nonlethal doses of pathogens, leaving open the question of whether the predator could save the animals’ lives.

Sockett needed to see evidence of survival improvement. “If we’re going to have Bdellovibrio as a medicine, we have to cure something,” she says. “We can count changes in numbers of bacteria, but if that doesn’t change the outcome of the infection — change the number of [animals] that die — it’s not worth it.”

So she teamed up with cell biologist Serge Mostowy of Imperial College London for a study in zebrafish. The aim was to see how many animals predatory bacteria could save from a deadly infection. The team also tested how the host’s immune system interacted with the predators.

The researchers gave zebra-fish larvae fatal doses of an antibiotic-resistant strain of Shigella flexneri, which causes dysentery in humans. Before infecting the fish, the researchers divided them into four groups. Two groups had their immune systems altered to produce fewer macrophages, the white blood cells that attack pathogens. Immune systems in the other two groups remained intact. B. bacteriovorus was injected into an unchanged group and a macrophage-deficient group, while two groups received no treatment.

All of the untreated fish with fewer macrophages died within 72 hours of receiving S. flexneri, the researchers reported in December in Current Biology. Of the fish with a normal immune system, 65 percent that received predator treatment survived compared with 35 percent with no predator treatment. Even in the fish with impaired immune systems, the predators saved about a quarter of the lot.

“This is the first time that Bdellovibrio has ever been used as an injected therapy in live organisms,” Sockett says. “And the important thing is the injection improved the survival of the zebrafish.”

The study also pulled off another first. In previous work, researchers had been unable to see predation as it happened within an animal. Because zebra-fish larvae are transparent, study coauthor Alexandra Willis captured images of B. bacteriovorus gobbling up S. flexneri.

“We were literally having to run to the microscope because the process was just happening so fast,” says Willis, a graduate student in Mostowy’s lab. After the predator invades, its rod-shaped prey become round. Willis saw Bdellovibrio “rounding” its prey within 15 minutes. From start to finish, the predatory cycle took about three to four hours.

The predator’s speed may be what gave it the edge over the infection, Mostowy says. B. bacteriovorus attacks fast, chipping away at the pathogens until the infection is reduced to a level that the immune system can handle. “Otherwise there are too many bacteria and the immune system would be overwhelmed,” he says. “We’re putting a shocking amount of Shigella, 50,000 bacteria, into the fish.”

Within 48 hours, S. flexneri levels dropped 98 percent in the surviving fish, from 50,000 to 1,000.

The immune cells also cleared nearly all the B. bacteriovorus predators from the fish. The predators had enough time to attack the infection before being targeted by the immune system themselves, creating an ideal treatment window. Even if the host’s immune system hadn’t attacked the predators, once the bacteria are gone, Willis says, the predators are out of food. Unable to replicate, they eventually die off.

A clean sweep

Predatory bacteria are efficient in more ways than one. They’re not just good killers — they eliminate the evidence too.

Typical antibiotic treatments don’t target a bacterium’s DNA, so they are likely to leave pieces of the bacterial body behind. That’s like killing a few bandits, but leaving their weapons so the next invaders can easily arm themselves for a new attack. This could be one way that multidrug resistance evolves, Mitchell says. For example, penicillin will kill all bacteria that aren’t resistant to the drug. The surviving bacteria can swim through the aftermath of the antibiotic attack and grab genes from their fallen comrades to incorporate into their own genomes. The destroyed bacteria may have had a resistance gene to a different antibiotic, say, vancomycin. Now you have bacteria that are resistant to both penicillin and vancomycin. Not good.

Predatory bacteria, on the other hand, “decimate the genome” of their prey, Mitchell says. They don’t just kill the bandit, they melt down all the DNA weapons so no pathogens can use them. In one experiment that has yet to be published, B. bacteriovorus almost completely ate up the genetic material of a bacterial colony within two hours — showing itself as a fast-acting predator that could prevent bacterial genes from falling into the wrong hands.

On top of that, even if pathogenic bacteria mutate, a common way they pick up new forms of resistance, they aren’t protected from predation. Resistance to predation hasn’t been reported in lab experiments since B. bacteriovorus was discovered in 1962, Mitchell says. Researchers don’t think there’s a single pathway or gene in a prey bacterium that the predator targets. Instead, B. bacteriovorus seem to use sheer force to break in. “It’s kind of like cracking an egg with a hammer,” Kadouri says. That’s not exactly something bacteria can mutate to protect themselves against.

Some bacteria manage to band together and cover themselves with a kind of built-in biological shield, which offers protection against antibiotics. But for predatory bacteria, the shield is more of a welcome mat.

Going after the gram-positives

When bacteria cluster together on a surface, whether in your body, on a countertop or on a medical instrument, they can form a biofilm. The thick, slimy shield helps microbes withstand antibiotic attacks because the drugs have difficulty penetrating the slime. Antibiotics usually act on fast-growing bacteria, but within a biofilm, bacteria are sluggish and dormant, making antibiotics less effective, Kadouri says.

But to predatory bacteria, a biofilm is like Jell-O — a tasty snack that’s easy to swallow. Once inside, B. bacteriovorus spreads like wildfire because its prey are now huddled together as confined targets. “It’s like putting zebras and a lion in a restaurant and closing the door and seeing what happens,” Kadouri says. For the zebras, “it can’t end well.”

Kadouri’s lab has shown repeatedly that predatory bacteria effectively eat away biofilms that protect gram-negative bacteria, and are in fact more efficient at killing bacteria within those biofilms.

Gram-positive bacteria cloak themselves in biofilms too. In 2014 in Scientific Reports, Mitchell and his team reported finding a way to use Bdellovibrio to weaken gram-positive bacteria, turning their protective shield against them and perhaps helping antibiotics do their job.

The discovery comes from studies of one naturally occurring B. bacteriovorus mutant with extra-scary spit. The mutant isn’t predatory. Instead of eating a prey’s DNA to make its own, it can grow and replicate like a normal bacterial colony. As it grows, it produces especially destructive enzymes. Among the mix of enzymes are proteases, which break down proteins.

Mitchell and his team tested the strength of the mutant’s secretions against the gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus. A cocktail of the enzymes applied to an S. aureus biofilm degraded the slime shield and reduced the bacterium’s virulence. Biofilms can make bacteria up to 1,000 times more resistant to antibiotics, Mitchell says. The next step, he adds, is to see if degrading a biofilm resensitizes a gram-positive bacterium to antibiotics.

Mitchell and his team also treated S. aureus cells that didn’t have a biofilm with the mutant’s enzyme mix and then exposed them to human cells. Eighty percent of the bacteria were no longer able to invade human cells, Mitchell says. The “acid spit” chewed up surface proteins that the pathogen uses to attach to and invade human cells. The enzymes didn’t kill the bacteria but did make them less virile.

No downsides yet

Predatory bacteria can efficiently eat other gram-negative bacteria, munch through biofilms and even save zebrafish from the jaws of an infectious death. But are they safe? Kadouri and the other researchers have done many studies, though none in humans yet, to try to answer that question.

In a 2016 study published in Scientific Reports, Kadouri and colleagues applied B. bacteriovorus to the eyes of rabbits and compared the effect with that of a common antibiotic eye drop, vancomycin. The vancomycin visibly inflamed the eyes, while the predatory bacteria had little to no effect. The eyes treated with predatory bacteria were indistinguishable from eyes treated with a saline solution, used as the control treatment. Other studies looking for potential toxic effects of B. bacteriovorus have so far found none.

In 2011, Sockett’s team gave chickens an oral dose of predatory bacteria. At 28 days, the researchers saw no difference in health between treated and untreated chickens. The makeup of the birds’ gut bacteria was altered, but not in a way that was harmful, she and her team reported in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

Kadouri analyzed rats’ gut microbes after a treatment of predatory bacteria, reporting the results in a study published March 6 in Scientific Reports. Here too, the rodents’ guts showed little to no inflammation. When they sequenced the bacterial contents of the rats’ feces, the researchers saw small differences between the treated and untreated rats. But none of the changes appeared harmful, and the animals grew and acted normally.

If the rats had taken common antibiotics, it would have been a different story, Kadouri points out. Those drugs would have given the animals diarrhea, reduced their appetites and altered their gut flora in a big way. “When you take antibiotics, you’re basically t hrowing an atomic bomb” into your gut, Kadouri says. “You’re wiping everything out.”

Both Mitchell and Kadouri tested B. bacteriovorus on human cells and found that the predatory bacteria didn’t harm the cells or prompt an immune response. The researchers separately reported their findings in late 2016 in Scientific Reports and PLOS ONE .

Microbiologist Elizabeth Emmert of Salisbury University in Maryland studies B. bacterio-vorus as a means to protect crops — carrots and potatoes — from bacterial soft rot diseases. For humans, she calls the microbes a “promising” therapy for bacterial infections. “It seems most feasible as a topical treatment for wounds, since it would not have to survive passage through the digestive tract.”

There are plenty of questions that need answering first. Mitchell guesses that there will probably be 10 more years of rigorous testing in animals before moving on to human clinical studies. But pursuing these alternatives is worth the effort.

“The drugs that we’re taking are not benign and cuddly and nice,” Kadouri says. “We need them, but they don’t come without side effects.” Even though a living antibiotic sounds a bit crazy, it might be the best option in this dangerous era of antibiotic resistance.