‘Pan-fashion’ approach transforms Zhejiang’s ‘sweater hometown’ Puyuan

As one of the official events of 2024 New York Fashion Week, a T-stage gala made its debut in Puyuan Town in East China's Zhejiang Province on Saturday. Known as the "hometown of knitted clothing" in China, Puyuan became a sensation when its sweater market turnover reached 130.4 billion yuan ($18.3 billion) in 2023.

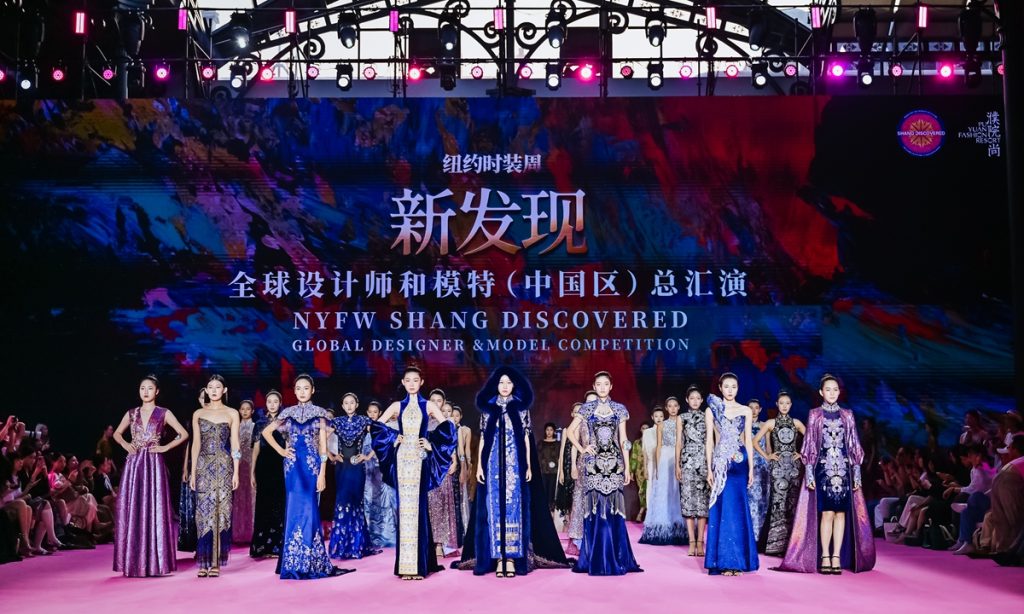

The show was called the NYFW Shang Discovered: Global Design & Model Competition. A total of 18 emerging designers and 60 models debuted at the town's Puyuan Fashion Resort, a cultural touristic landmark known for its antique-looking architecture in Tongxiang, East China's Zhejiang Province.

The gala featured garments made from the local intangible cultural heritage known as "Pu silk." Ma Jianrong, the chairman of the event's organizing committee, told the Global Times that the gala not only exhibits the "indigenous yet inclusive Chinese aesthetics to the world," but also shows how Puyuan is using "fashion" as a strategy for its modern development.

"At this show, we want people to see how fashion has boosted the region's industrial growth as well as nurtured opportunities in sectors like cultural tourism," Ma emphasized.

Puyuan's sweater manufacturing tradition emerged during the 1970s with only a few hand-operated flat knitting machines and a few merchants. Now, the 60.5-square-kilometer town has more than 13,000 business units. Its all-round and modernized industrial chain makes it China's largest production base for knitted clothing.

Over 40 years of development, the local knitting industry, especially its cashmere and sweater sectors, has blossomed. Around 700 million sweaters made in Puyuan Town are sold annually worldwide. Such a record is still expecting new growth due to the nearby Jiaxing Nanhu Airport that is under construction.

"We have a powerful and well-established manufacturing base here, and now we are looking to transform it into 'Puyuan Fashion' through a pan-fashion strategy," Zhou Yan, member of the Standing Committee of the CPC Tongxiang committee and the Party secretary of Puyuan Town of the People's Government of Tongxiang, told the Global Times.

Taking the NYFW Shang Discovered show as an example, the pan-fashion strategy suggests "broadening the concept of fashion" and combining it with cultural creative industries, tourism, the fashion industry and also the younger generation's preferred sectors like esports.

The Puyuan Fashion Resort is where this pan-fashion blueprint is being fulfilled.

The resort, which carries South China's typical above-water gardening and architectural aesthetics, has brought in more than 1 million tourists since it was opened in 2023. It is now a Puyuan landmark that hosts fashion shows every year. It also has events dedicated to esports and the streaming industry planned for the latter half of the year.

Yao Jie, a representative who is in charge of the resort's management sector, told the Global Times that in the future a Coca-Cola experiential center is planned for the resort with the aim of attracting young visitors. Also, the resort is planning to dedicate a block to incorporate cultural and creative commercial units with original designs.

"Our target consumers are young people of course, but also people pursuing fashionable lifestyles regardless of their age," Yao remarked. She also emphasized that tourists make huge contributions to the local clothing retail market.

The approach of using the increasing number of tourists to promote itself while boosting sales is just one goal of its development plan for the next five years.

Giving his insight, Zhou told the Global Times that "Puyuan Fashion" will aim to go abroad by "bringing in overseas design brands while encouraging local brands to join international exhibitions."

"Our aim is to make the world know that any knitted product with a Puyuan tag is one of the top-notch products in the world," Zhou remarked.