See these first-of-a-kind views of living human nerve cells

The human brain is teeming with diversity. By plucking out delicate, live tissue during neurosurgery and then studying the resident cells, researchers have revealed a partial cast of neural characters that give rise to our thoughts, dreams and memories.

So far, researchers with the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle have described the intricate shapes and electrical properties of about 100 nerve cells, or neurons, taken from the brains of 36 patients as they underwent surgery for conditions such as brain tumors or epilepsy. To reach the right spot, surgeons had to remove a small hunk of brain tissue, which is usually discarded as medical waste. In this case, the brain tissue was promptly packed up and sent — alive — to the researchers.

Once there, the human tissue was kept on life support for several days as researchers analyzed the cells’ shape and function. Some neurons underwent detailed microscopy, which revealed intricate branching structures and a wide array of shapes. The cells also underwent tiny zaps of electricity, which allowed researchers to see how the neurons might have communicated with other nerve cells in the brain. The Allen Institute released the first publicly available database of these neurons on October 25.

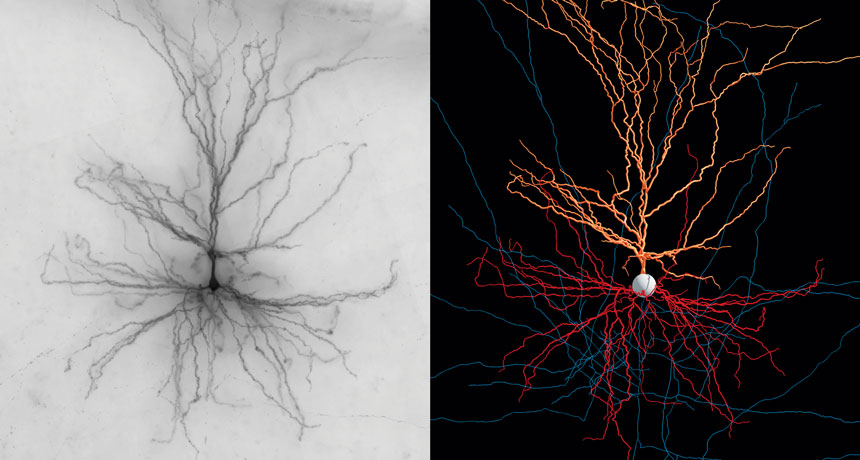

A neuron called a pyramidal cell, for instance, has a bushy branch of dendrites (orange in 3-D computer reconstruction, above) reaching up from its cell body (white circle). Those dendrites collect signals from other neural neighbors. Other dendrites (red) branch out below. The cell’s axon (blue) sends signals to other cells that spur them to action.

Like the chandelier cell, a Martinotti cell (below) quiets other cells with messages coming from its tangled, tall axon, which spans several layers of the brain’s cortex — the wrinkly, outer layer that’s involved in higher-level thought. And in a basket cell (above), axon branches, which allow the nerve cell to send messages to other neurons, cluster densely around the cell body.

Because the neurons play different roles in the brain, the new collection could help researchers figure out the details of those diverse jobs. Similar data exist for cells taken from the brains of other animals, such as mice, but until now, data on live cells from people have been scarce.

“These neurons are amazingly beautiful,” says Ed Lein, a neuroscientist at the Allen Institute who works on the project. “They look like trees. They’re much more complex than similar cells in a mouse.”